A brief summary of everything you need to know about annuity death benefits and payout options:

- How an annuity works after death depends on whether the annuity 1) was owned individually or jointly, 2) includes a death benefit, and 3) the type of beneficiary provided there is a death benefit.

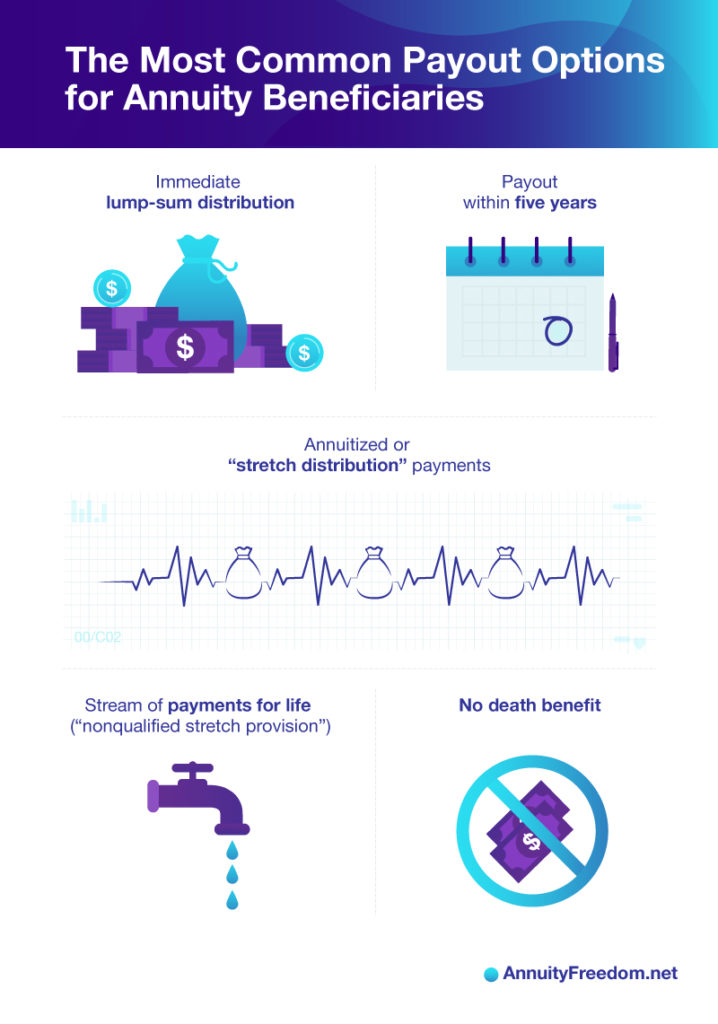

- The most common payout methods for annuity beneficiaries are immediate lump-sum distribution, payout within five years, payments over time, and payments for life.

- Taxes responsibilities for beneficiaries are influenced by whether the annuity was funded with pre-tax or after-tax dollars.

- People who inherit an annuity may sell future payments for cash.

Selling your annuity?

Most people buy annuities to create a guaranteed stream of income in their golden years that can augment their Social Security or pension (for those dwindling few who have one). But that’s not the only consideration. Annuities can provide a means of taking care of loved ones if the person who purchased those annuities, known as the annuitant, dies.

Most annuity owners designate beneficiaries. Typically, these conditions apply:

- Owners can choose one or multiple beneficiaries and specify the percentage or fixed amount each will receive.

- Beneficiaries can be people or organizations, such as charities, but different rules apply for each (see below).

- Owners can change beneficiaries at any point during the contract period.

- Owners can choose contingent beneficiaries in case a would-be heir passes away before the annuitant.

What Happens With an Annuity When You Die?

It depends on the structure and terms of the annuity, but here are some of the most common scenarios:

1. Jointly owned annuity

There is a difference between a co-owner and a beneficiary. If a married couple owns an annuity jointly and one partner dies, the surviving spouse would continue to receive payments according to the terms of the contract. In other words, the annuity continues to pay out as long as one spouse remains alive.

These contracts, sometimes called joint and survivor annuities, can also include a third annuitant (often a child of the couple), who can be designated to receive a minimum number of payments if both partners in the original contract die early. If you’ve inherited an annuity, check to see whether it falls into this category.

Here’s something to keep in mind: If an annuity is sponsored by an employer, that business must make the joint and survivor plan automatic for couples who are married when retirement occurs. A single-life annuity should be an option only with the spouse’s written consent.

If you’ve inherited a jointly and survivor annuity, it can take a couple of forms, which will affect your monthly payout differently:

- 100% survivor annuity. In this case, the monthly annuity payment remains the same following the death of one joint annuitant. The death doesn’t affect the amount received. This kind of annuity might have been purchased if:

- The survivor wanted to take on the financial responsibilities of the deceased.

- A couple managed those responsibilities together, and the surviving partner wants to avoid downsizing.

- 50% survivor annuity. The surviving annuitant receives only half (50%) of the monthly payout made to the joint annuitants while both were alive. This kind of annuity might have been chosen if the two partners managed their financial responsibilities separately, and the surviving spouse did not wish to continue other partner’s obligations (such as club memberships, individual insurance payments, hobby expenses, and so forth).

2. Spouse beneficiaries

Many contracts allow a surviving spouse listed as an annuitant’s beneficiary to convert the annuity into their own name and take over the initial agreement. In this situation, known as spousal continuation, the surviving spouse becomes the new annuitant and collects the remaining payments as scheduled.

Spouses also may elect to take lump-sum payments or decline the inheritance in favor of a contingent beneficiary, who is entitled to receive the annuity only if the primary beneficiary is unable or unwilling to accept it.

Tax consequences vary depending on the course of action the surviving spouse takes, but inheriting a spouse’s annuity does not automatically become a taxable event. Cashing out a lump sum will trigger varying tax liabilities, depending on the nature of the funds in the annuity (pretax or already taxed). But taxes won’t be incurred if the spouse continues to receive the annuity or rolls the funds into an IRA.

3. Minor beneficiaries

It might seem odd to designate a minor as the beneficiary of an annuity, but there can be good reasons for doing so. Some children with physical or developmental disabilities may need a stream of income to help them get care throughout their lives. In other cases, a fixed-period annuity may be used as a vehicle to fund a child or grandchild’s college education.

Minors can’t inherit money directly. An adult must be designated to oversee the funds, similar to a trustee. But there’s a difference between a trust and an annuity: Any money assigned to a trust must be paid out within five years and lacks the tax advantages of an annuity.

A minor designated as the beneficiary of an annuity can access the inherited funds only when he reaches the age of 18. The beneficiary may then choose whether to receive a lump-sum payment.

4. Other beneficiaries

A non-spouse cannot typically take over an annuity contract. One exception is “survivor annuities,” which provide for that contingency from the inception of the contract. One consideration to keep in mind: If the designated beneficiary of such an annuity has a spouse, that person will have to consent to any such annuity.

What to Know if You Inherit an Annuity

Payout options

Depending on the terms of the annuity, there might be different payout options available to beneficiaries. You will need to review the specific contract for precise details, but these are some of the most common scenarios.

Distribution options explained

- Lump-sum distribution — A lump sum is the remaining contract value or a guaranteed amount. In terms of a loan, it’s called a “bullet payment,” as opposed to installments. Lump sums are paid all at once and can be useful to a beneficiary seeking to make a major purchase, such as a home or major business investment. But there are tax consequences because they have to pay the IRS on the entire taxable sum at once.

- Payout over five years — Under the “five-year rule,” beneficiaries may defer claiming money for up to five years or spread payments out over that time, as long as all of the money is collected by the end of the fifth year. This allows them to spread out the tax burden over time and may keep them out of higher tax brackets in any single year.

- Annuitized or “stretch distribution” payments — A stretch provision is just what it sounds like: It allows a beneficiary to stretch payments — along with the tax consequences — from an inherited annuity out over the span of his or her own life expectancy. Once an annuitant dies, a nonspousal beneficiary has one year to set up a stretch distribution.

- Stream of payments for life (nonqualified stretch provision) — This format sets up a stream of income for the rest of the beneficiary’s life. Because this is set up over a longer period, the tax implications are typically the smallest of all the options.

- No death benefit — If there is no beneficiary or annuity death benefit provision, any funds left in the contract at the time of death may revert to the insurance company. This is sometimes the case with immediate annuities — which can start paying out immediately after a lump-sum investment — without a term certain.

Important: Estates, trusts, or charities that are beneficiaries must withdraw the contract’s full value within five years of the annuitant’s death.

Tax implications to Consider

- Taxes are influenced by whether the annuity was funded with pre-tax or after-tax dollars. Annuities funded by money that’s already been taxed are nonqualified. This simply means that the money invested in the annuity — the principal— has already been taxed, so it’s nonqualified for taxes, and you don’t have to pay the IRS again. Only the interest you earn is taxable.

- On the other hand, the principal in a qualified annuity hasn’t been taxed yet. Often, it’s been rolled over from a 401(k) or IRA. So when you withdraw money from a qualified annuity, you’ll have to pay taxes on both the interest and the principal.

- Proceeds from an inherited annuity are treated as gross income by the Internal Revenue Service. Gross income is income from all sources that are not specifically tax-exempt. But it’s not the same as taxable income, which is what the IRS uses to determine how much you’ll pay. Taxable income is the figure you get after subtracting allowable deductions.

- If you inherit an annuity, you’ll have to pay income tax on the difference between the principal paid into the annuity and the value of the annuity when the owner dies. For example, if the owner purchased an annuity for $100,000 and earned $20,000 in interest, you (the beneficiary) would pay taxes on that $20,000. How and when you cash out your annuity determines when you’ll pay those taxes and how much the income will affect your overall tax liability.

- Lump-sum payouts are taxed all at once. This option has the most severe tax consequences, because your income for a single year will be much higher, and you may wind up being pushed into a higher tax bracket for that year.

- Gradual payments are taxed as income in the year they are received. If you, as the beneficiary, choose to take gradual payments, it’s less likely you’ll be bumped up to a higher tax bracket for any given year.

- In some circumstances, if payments continue under a life annuity, the money is not taxed until the total that’s distributed exceeds the initial cost of the contract. (Be sure to consult a tax professional for advice.)

Probate

Designating a beneficiary for an annuity can protect the heirs from probate, a formal legal process that recognizes a will and appoints the executor to oversee the distribution of assets. One problem with probate is that, like most things involving the courts, it can take a long time. How long? The average time is about 24 months, although smaller estates can be disposed of more quickly (sometimes in as little as six months), and probate can be even longer for more complex cases.

Having a valid will can speed up the process, but it can still get bogged down if heirs dispute it or the court has to rule on who should administer the estate.

An annuity can be used to bypass probate if it names a specific beneficiary. Because the person is named in the contract itself, there’s nothing to contest at a court hearing. It’s important that a specific individual be named as beneficiary, rather than merely “the estate.” If the estate is named, courts will examine the will to sort things out, leaving the will open to being contested.

Another factor annuitants should consider is whether they want to name a contingent beneficiary. This may be worth considering if there are legitimate worries about the person named as beneficiary passing away before the annuitant. Without a contingent beneficiary, the annuity would likely then become subject to probate once the annuitant dies. Talk to a financial advisor about the potential advantages of naming a contingent beneficiary.

Factors That Influence Death Benefits

Type of annuity

Is the annuity immediate or deferred, fixed, or variable? Such factors can be important in determining what death benefits, if any, a surviving beneficiary can receive.

- Immediate vs. Deferred

- Immediate annuities usually don’t carry a death benefit. They’re created by a lump-sum payment and can begin paying out immediately (hence the name). They’re generally used by older people who want to create an immediate secondary stream of income for their retirement. One downside, at least for their heirs, is that if the annuitant dies before the money’s used up, family members won’t be able to access the money. Instead, it generally reverts to the insurance company, which puts it in a pool to pay out other clients who may have outlived the money they invested.

- Deferred annuities, unlike immediate annuities, typically include a death benefit for beneficiaries, who receive what’s left in the account or a guaranteed minimum. Deferred annuities delay payments until a future date, usually two to 30 years down the line, which gives the investment a chance to grow. Because of this lag time, they’re generally purchased by younger people who don’t need an immediate benefit but want to invest for retirement. They can be funded by lump sums or a series of deposits. A beneficiary can be designated and will receive whatever’s left in the account at the time of the annuitant’s death, or a guaranteed minimum.

- Lifetime vs. Fixed-period

- Lifetime annuities guarantee a stream of income for the rest of the annuitant’s life, however long that may be, or for the life of the annuitant and their spouse if they purchase a joint lifetime annuity. Absent a joint-and-survivor provision, however, the annuitant is the only one who can benefit. Think of it as a personal contract designed to benefit the annuitant alone. They set up a contract to receive regular payments depending on how much was invested and how soon they start receiving those payments. The more money that was put in, and the later the payments were started, the larger those payments will be. But the contract terminates at death. If the annuitant purchases a lifetime annuity, it means they can’t outlive their income stream, but it also means the heirs won’t get to claim the benefit after the annuitant’s gone.

- Fixed-period annuities, also called period-certain annuities, pay out over a finite period of time. If, for instance, the annuitant chooses a 15-year contract, they’ll get payments for that period, but they’ll end after 15 years. As a result, they may possibly outlive their benefits. On the flipside, though, if they die before the contract expires, the money can pass to a designated beneficiary.

3. Fixed vs. Variable

- Fixed annuities pay at a guaranteed interest rate but offer a relatively modest rate of return. If you inherit a fixed annuity, you’ll know what you’re getting in terms of growth.

- Variable annuities use mutual funds to maximize growth, but they also carry greater risk: If the market declines, so will the value of your annuity. If you inherit a variable annuity and the mutual funds in the contract are performing poorly, it won’t be worth as much when you receive it as it would have been during a bull market.

Standard death benefit

The standard death benefit is straightforward: It pays the current value of the annuity contract to the beneficiary, regardless of whether it’s gone up or down since the initial purchase.

This may be modified with a return of premium option that guards against market volatility. This costs extra but gives the beneficiary the greater of these two payouts:

- The contract’s market value.

- The total of all contributions, once fees and withdrawals are subtracted.

It’s important to note that the size of the premium being returned will be less than it was initially, depending on how much of it the original annuitant has taken in payments. This is what’s called a declining benefit. For instance, if the annuitant purchased a $400,000 lifetime annuity and took $20,000 in payments for each of the first three years, that would leave $340,000 for the beneficiaries. If instead the annuitant took $150,000 of it total in the first three years, there would only be $250,000 left for their beneficiaries.

Return of premium is one of several bonus clauses, called riders, that can be purchased for additional fees, some of which are aimed specifically at protecting beneficiaries.

Optional riders

Riders are optional clauses in an annuity contract that can be used to tailor it to specific needs. They come at an additional cost because they typically provide an additional level of protection. The more riders purchased, the higher the price is to pay: Each rider typically costs between 0.25% and 1% annually.

- Return of premium, mentioned above, is a rider that can be purchased as protection against dying before all the money invested in a lifetime annuity is paid out to the annuitant. Without such a rider, the remaining money would revert to the insurance company, to be pooled with funds for other lifetime annuity holders who might outlive the amount they’d invested. It wouldn’t go to the heirs. (This is a trade-off for the insurance company because some annuitants will outlive their investments, while others will die early. Theoretically, at least, it balances out.)

A return-of-premium rider can ensure that the money paid in will be passed along to the heirs if the annuitant dies early. It costs extra because the insurance company needs something to offset the money it might otherwise use for its pool. Is this added cost worth it? If the annuitant is in good health and thinks they might use up all or most of the premium before they die, it might not be. It’s important to talk to a financial consultant and check out all the angles. - Stepped-up death benefit rider, known as an SDBR for short, “steps up” its amount monthly or annually to lock in the value of the account. Under this rider, the insurance company records the value of the annuity each month (or year), then uses the highest figure to determine the benefit when the annuitant dies. An SDBR protects beneficiaries of variable annuities against market fluctuations: If the value happens to be down at the time of death, the beneficiary still gets the top-line amount.

Like other riders, however, this one comes at a cost. The price of enhanced death benefits can range from 0.25% to 0.5% of the account value each year, and it can add up. It’s important to talk to a financial counselor to guard against paying more money than would likely be saved.

Lottery annuities

A lottery annuity, as you might expect, applies to lottery winners, who have a choice to accept their Powerball, Mega Millions, or state lottery proceeds as a lump sum or via installments.

The installment option is a form of annuity, although it’s different from a typical annuity in that it hasn’t been set up or sold by an insurance company. But the securities behind the lottery payout are backed by the U.S. government, which actually makes them safer than any privately backed annuity.

Electing to take annuitized installment payments for lottery winnings can have a couple of advantages:

- It can guard against the temptation to overspend or overextend on obligations, which may result in financial difficulties or even bankruptcy down the road.

- As with any other annuity, taking payments over time, rather than in a lump sum, stretches out and minimizes the tax liability (keeping the winner out of higher tax brackets). If the winner takes a lump sum, the lottery commission typically withholds 25% of the winnings for federal taxes, leaving the winner with the task of settling the actual amount on April 15. Some states levy taxes on lottery winnings, while others don’t. It’s a good idea for winners to check their state’s policy before deciding how to accept their winnings.

FAQs About Annuity Beneficiaries

What’s the difference between buying and inheriting an annuity?

You can become an annuitant either by purchasing an annuity or by inheriting one. If you buy an annuity, you can set the terms of the annuity contract, decide what kind of annuity to purchase, choose whether you want riders, and make other decisions. If you inherit an annuity, you may not have the same options, especially if you weren’t a spouse with joint ownership.

If you’ve inherited an annuity but are not a surviving spouse, you can:

- Choose, within 60 days, to annuitize the contract over the span of your own lifetime.

- Take a lump-sum payout.

- Take the full payout over the next five years under the five-year rule.

Can more than one beneficiary be named?

Yes. An annuitant can name a primary beneficiary and a contingent beneficiary, but also can name more than one in either category. There’s actually no limit to the number of primary or contingent beneficiaries that can be named. If the annuitant elects to name multiple beneficiaries, however, they must designate a specific percentage for each one in the same class. And (sorry, pet lovers), Fido or Floofer can’t be named as a beneficiary. Neither can a pet rock or other inanimate object.

Can I sell an inherited annuity?

Yes. An inherited annuity can provide money for the beneficiary to pay off major expenses (such as student debt, a mortgage, health-care costs, etc.). If you decide to sell your inherited annuity, you can do so in one of three ways:

- Sale in entirety — You can sell all your scheduled payments for the remainder of the annuity contract term and receive a lump-sum payment in exchange.

- Partial sale (specific period) — You can sell a specific period of the remaining annuity in exchange for a lump sum. For example, if you have 15 years remaining on your inherited annuity, you can sell the first five years and receive a lump sum for that. After those five years are up, payments will resume.

- Partial sale (partial payments) — If you prefer not to wait for payments to start up again, but you need some money now, you can sell a portion of each payment and receive a lump sum. In this case, your payments will continue uninterrupted, but each of the payments will be smaller than they were before the sale.

If you need a large sum of money, selling your annuity can be an option worth exploring. You might also have considered taking out a loan, but remember:

- Any loan you take out is a new long-term obligation; if you sell your annuity, the only obligation you’ll have is short-term, in the form of potential tax liabilities and surrender fees.

- If you take out a loan, you’ll be working with someone else’s money; the cash you get from selling your annuity will be yours outright.

- Late payments or loan defaults can lead to bad credit scores, or even bankruptcy and foreclosure. Even if you’re in good financial shape now, an unforeseen crisis (loss of job, medical expenses, etc.) can put you behind the 8-ball if you’re stuck with big loan payments. You don’t face those risks if you sell your annuity.

- Loans come with sometimes hefty interest rates. Depending on your credit, the term of the loan and other factors, you could end up paying almost as much in interest as you received through the loan. For example, a 30-year mortgage worth $200,000 would cost you a total of more than $343,000 when all is said and done.

Check with your financial advisor and weigh your options.

How does divorce affect annuity inheritance?

The answer to this question depends on several factors. Among the most important is when the annuity was purchased. If you purchased an annuity before your marriage, it may be considered your separate property and not eligible to be divided by the court. However, an annuity purchased during the marriage may be viewed, legally, as community property and subject to division.

Another factor: If the annuity originally was part of an inheritance and wasn’t commingled into a joint account, the court will probably view it as your separate property that can’t be divided.

If a court decides an annuity is community property, how is it divided?

Dividing an annuity in a divorce can have severe tax consequences. Some divorce attorneys may not know the risks of doing it wrong. It’s imperative that you also speak to a financial advisor about the potential ramifications in crafting any settlement.

If you own a qualified annuity — perhaps it was part of a pension, 401(k), or other employer-sponsored retirement plan funded with pre-tax dollars — you will need a qualified domestic relations order (QDRO). This is a court order that outlines the payment of child support, alimony, or other divorce-related property. No QDRO is required if you’re dividing a nonqualified annuity (funded with after-tax dollars).

The court, however, cannot award either divorcing party income or benefits from an annuity that are not available under the original contract. For instance, an annuity can’t simply be cashed out in a lump sum and divided 50-50 if the contract doesn’t allow it.

A bit of good news: Even though the law calls for a 10% penalty on distributions from an annuity before age 59½, that law does not apply to transfers made to an ex-spouse in a divorce.

When it comes down to actually dividing an annuity in a divorce settlement, an annuitant has four choices:

- Withdraw money from the annuity and take a direct distribution.

- Transfer the amount directly to an IRA.

- Take a withdrawal from the original annuity and create two new contracts, one for each spouse, that define new benefits and account values.

- Transfer the contract’s ownership to a single spouse, creating a new contract.

What does “per stirpes” mean?

“Per stirpes” is a Latin term that means, literally, “my branch.” Insurance companies usually will allow an annuitant to designate any beneficiary as “per stirpes.” This means that the beneficiary’s share of the annuity proceeds would pass on to heirs if the beneficiary dies before the contract holder.

What is ERISA and what does it cover?

ERISA, or the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, was passed in 1974 to protect retirement savings and applies specifically to retirement plans sponsored by private employees.

The SECURE Act of 2019 added a “safe harbor” protection to ERISA which encourages employers to offer annuities as a retirement-plan option. It does so by limiting employers’ responsibility for the failure of insurance companies to live up to their annuity contracts.

Under this amendment, the employers cannot be held liable for “any losses that may result to the participant or beneficiary due to an insurer’s inability to satisfy its financial obligations under the terms of the contract.”

Check with your financial advisor to find out the implications of taking an annuity option from your employer and how it may affect you and your beneficiaries.

What’s the difference between a designated and non-designated beneficiary?

A designated beneficiary is an individual, such as a spouse, child, or other human being. A non-designated beneficiary is an entity such as a charity, trust, or estate. Non-designated beneficiaries are subject to the five-year rule when it comes to annuities.

Conclusion

So, if you inherit an annuity, what should you do? The answer depends on a variety of factors linked to your financial situation and personal goals.

Maybe you need a lump sum to start a business, buy a home, or make another large purchase. If so, you might consider taking the money all at once. There’s certainly peace of mind in owning your own home; you’ll have to pay property taxes, but you won’t have to worry about landlords raising the rent or sticking their nose in your business. (We all know how much fun that is.)

The tax liability and penalties you incur by cashing in your annuities all at once could be offset by the profits from that new business or the appreciation value on a home. Then again, you might wind up losing a significant amount of money if the real estate market is flat or your business doesn’t do as well as you hoped. So keep that in mind. One of the benefits of annuities is that, as long as the company backing them is reputable and healthy, you’ve got a guaranteed stream of income. You’ll lose that if you cash out.

That’s why, if you don’t need the money right away, it might be smarter to save the inherited annuity to help bolster your future financial security. It also could decrease your tax liability. But selling your annuity can be a good option — and an appealing alternative to taking out a loan — if you need a large chunk of cash. Before deciding anything, it’s always a good idea to seek advice from a licensed financial advisor.